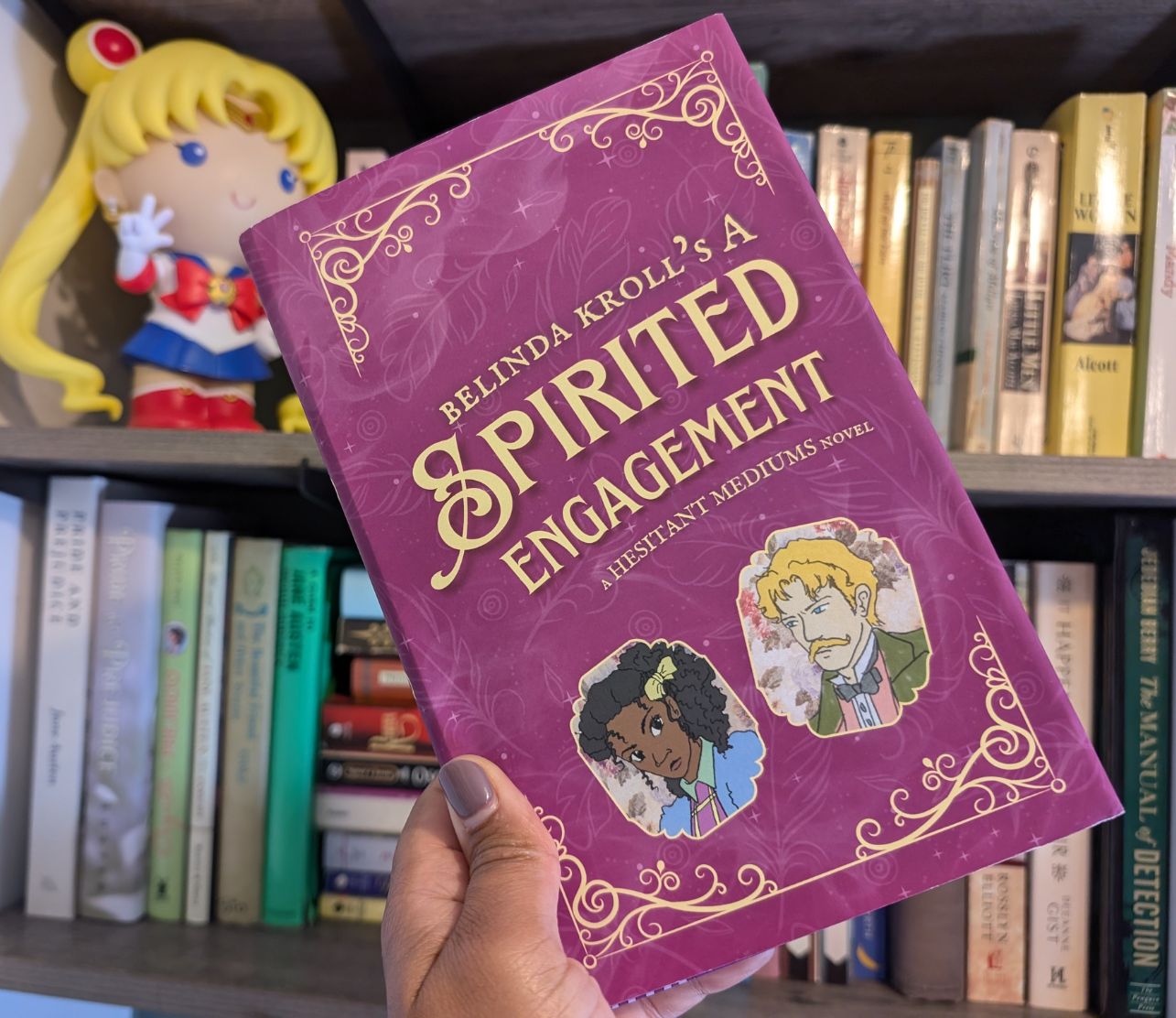

Haunting Miss Trentwood, an excerpt

Compton Beauchamp, February 1887

Three days' ride West of London

At two in the afternoon the coffin of Mary Trentwood’s father was lowered to its grave. The sun shone unseasonably bright. Mary squinted through burning eyes. She heard the wooden box hit the bottom of the hole. She heard the whispers of her servants and father’s friends behind her. However quietly they thought they were speaking, Mary heard every word. The whispers grew louder and moved closer, crowding her ears.

“Right barmy, that’s what she is.”

“I heard she hasn’t any feeling at all.”

“Certainly would explain the lack of tears.”

“Making us stand here and watch the digging of the grave, it’s indecent, that’s what it is.”

“Well, I certainly don’t know how you can expect any better from hermits, they’re not fit to be gentry, I say.”

Mary didn’t know who they were, these people whispering about her as she stood a mere four feet in front of them. She didn’t care. They weren’t there for her, they—whoever they were for she hadn’t invited them, no, that had been the workings of her aunt Mrs. Durham—only cared about their gossip mongering. The local farmers and tenants would never treat her thus. But the funeral guests were certain to spread their hissing rumors across the countryside. Mary hated that unnamed mass of huddled, whispering heads standing behind her. She hated her father for dying, for making this entire ordeal necessary in the first place.

The vicar finished his sermon and snapped his Bible shut.

Mary hunched her shoulders as the mourners filed past. She gritted her teeth, but allowed the men to solemnly brush their lips against her gloved fingers. Her jaw all but shattered in her effort to not scream at the women making tut-tutting noises.

And then Mary was alone, her black netted veil scratching her pale cheek as the wind blew. She stared at that father-sized hole. She stepped closer. How close to the edge did she dare tread? How soon before her nerves, strained to their last, snapped, rendering her as lifeless as her dear father at the bottom of that dark pit?

Mary jumped when Mrs. Durham’s hand touched her arm.

Mrs. Durham was a squat woman, with soft features that hinted at great beauty, once. Once upon a time, a very long time ago, Mary figured. Mrs. Durham had been her mother’s twin, fraternally speaking. Mary was glad she didn’t resemble her aunt in the slightest. Mrs. Durham’s cheeks arched upward—reaching, straining, pushing—trying to touch the topmost curve of her eye sockets. Truly an appalling sight; Mary decided her aunt should never squint, if she could help it.

“Come away,” Mrs. Durham murmured, “let the men folk do their job.” She shifted so Mary’s view of the gravediggers filling the grave was blocked. She began pushing Mary back to the manor house, where a light luncheon waited for them.

Whatever suggestive power Mrs. Durham had on Mary could not prevent the horrifying vision of a man, muddy and coughing, clawing his way from the grave site. He hung from the edge of the hole into which Trentwood’s coffin had descended, his elbows digging into the dirt as he wriggled his way out.

Mary stared open-mouthed.

He was dismayingly flexible, able to swing a leg over the edge and roll onto the disturbed ground. He stood, brushing himself off almost apologetically though no dirt clung to his clothing. He gave Mary time to study his determined chin, firm mouth, and snappish eyes. He combed his sandy hair back from his forehead while clearing his throat, revealing streaks of gray running from temple to crown. The overall effect was chilling familiarity.

Mary wrenched free of Mrs. Durham. “Father?” she said, her voice hoarse from not speaking the week since his death. “Papa?”

Mary sat upright, kicking her bed sheets away from sweat-soaked legs. A lock of her dark hair was plastered to her cheek. Her head ached from the bobby pins still shoved into her scalp. She lifted her hand to pull the bobby pins out and noticed she was wearing black crepe sleeves, the same she wore in her nightmare.

Her hands shook. She hadn’t been dreaming. Mary knew she hadn’t been dreaming. She had buried her father, and he had crawled from his grave right before her eyes.

Her bedroom door opened to reveal Mrs. Durham with a tray of tea. “Oh good,” Mrs. Durham said with false cheer, “you’re finally awake.”

“Finally?” Mary said. Her voice was no more than an awkward croak, but it seemed Mrs. Durham understood her.

“You’ve been sleeping for three days.”

Mary shook her head. She gasped. Three days? Had it been three days since she had buried her father? Panting, she unbuttoned her dress to her collar bone, unable to inhale with the neck buttoned to her chin. She felt so hot. Why hadn’t anyone undressed her? Right, that’s right, she had dismissed her maid after her father died to alleviate costs.

Mary shook her head again as Mrs. Durham placed the tea tray on the little table beside her bed. Everything felt fuzzy.

Mrs. Durham sat in the vanity chair that had been dragged to the bedside while Mary slept. Her black dress rustled sweetly as she moved, the fabric shining in the gray sunlight. “You fainted dead away after the coffin went down.”

Mary sighed. “Yes, I just—I thought I saw Papa.”

“But you did, my dear.”

Mary’s hazel eyes narrowed to slits. “I did?”

“Well, do forgive my callousness, but I’m not certain who else you think we buried.”

Mary felt a retort forming, but she held her tongue. She had to remember her aunt had lost her dear husband only four months ago, and was still out of sorts. She took the time to study Mrs. Durham shiny black earrings, the way her hands folded in her lap, the perfection of her graying hair pulled into a tight chignon topped with white lace.

Do I tell her? Do I admit I saw Father crawl from his grave? No, Mrs. Durham was not one for believing such “folderol” as she called it when Mary confided her nightmares or shared folklore and haunting stories with the servants.

Mary looked at the bedroom door, not hearing the raucous laughter of the funeral guests. “Where is everyone?” Mary asked instead, accepting a lukewarm cup of tea.

“Ah, I sent them home. Well,” Mrs. Durham chuckled, “they left fairly quickly on their own. They were quite startled when you announced you wanted everyone to follow the coffin to its grave. What in the world made you do such a thing? It simply isn’t done.”

No, it wasn’t done, but then, there were a great many things that Mary had done to satisfy Society, and she had decided that Society, in turn, could grant her this one aberration. Mary swallowed the last of the tea and placed the cup on the tray. “I’m rather tired.”

Mrs. Durham frowned, hearing the finality in Mary’s tone. “Of course,” she replied, standing. “I trust you will send for me should you need me?” At Mary’s silent nod, she took her leave, looking none too pleased.

As soon as the door was shut, Mary threw her hands to her face. “I did not see my father’s ghost.” She shivered despite being drenched with sweat. “I must be mad.”

“A bit dramatic, I suppose, but mad? Would I allow you to run my household if you were mad?”

Mary screamed. She grabbed her skirts and scrambled atop her headboard.

At the foot of her bed stood her father. At least, she thought it was her father. It certainly looked just like him. Trentwood stood as he always had when lecturing her, hands clasped behind his back with a stern look on his face. “So you didn’t see me, eh?”

In which a father returns

Mary remained where she was, clinging to her headboard and staring at Trentwood. She shook her mind free of the memories from that horrible night over a year ago. There was nothing to be done about that now. Steele had never called, and she hadn’t the time for courting anyway, not with her father so ill. And now that her father had died—and his ghost was standing at the foot of her bed—well, that didn’t make her future chances at courtship seem any brighter.

Practically speaking, of course.

Mary’s mouth wavered between hysterical laughter and another scream. Her father was dead, and she wanted—needed—to mourn him. She wanted to remember him fondly and cry herself to sleep over her loss. She did not want to be crawling away, terrified of this vision that was her father.

It wasn’t right or decent, this horror replacing sorrow.

She swallowed, biding her time, waiting for words to come. Did ghosts need to sit? Or was it merely the principle of the matter? Her father had been, if nothing else, concerned with the principle of the matter. Did such things carry over into the afterlife?

“Aren’t you growing rather tired of hanging from that headboard as if you were some primate?” Trentwood said.

Mary dropped to her knees. She landed with little grace in the jumble of sheets piled atop her bed. She couldn’t take her eyes from Trentwood. His fingers were grimy, most likely from his unearthly climb. He smelled of earth and age and disease, spiced with a hint of peppermints—his favorite treat.

“There now, isn’t that better?” Trentwood looked as he had in his life but for his eyes, the irises particularly. They had lost almost all pigmentation, so that the dark hazel she had inherited looked an insipid beige.

She scowled. A knock at the door startled her from responding.

“Miss Trentwood?” It was Pomeroy, Trentwood’s valet-cum-butler. His voice was gentle, but firm, as he said, “I happened to be in the hallway just a moment ago and had the oddest idea I heard you scream. Might I come in and inquire?”

Mary cleared her throat and dragged her gaze from Trentwood. “No, thank you,” she said, raising her voice so Pomeroy could hear her. “I thought I saw… er, there was—”

As Mary scanned the room looking for an excuse for screaming, she caught sight of Trentwood looking rather smug while he waited for her reason. She pressed her lips together. He was having fun with this! She crawled from her bed and backed to the door. Her chin jutted out, and she glanced at Trentwood, noting the way his brows rose.

It was easier to breathe by the door, Mary couldn’t smell Trentwood. She pressed her cheek to the carved wooden door that kept Pomeroy from entering. She breathed the warm smell of old wood, relishing in its solidity. She needed to convince herself she was grounded, sane, normal.

“I had a nightmare,” Mary said, “and frightened myself awake. Please don’t concern yourself, it was very silly.”

She heard Pomeroy clear his throat and imagined him shifting his weight from one foot to the next as he searched for the most proper way to voice his thoughts.

“Shall I ask Mrs. Durham to keep you company?”

Mary closed her eyes. “No, thank you.”

“Shall I keep you company, Miss?”

Now that was an interesting thought, to allow Pomeroy enter. Especially with Trentwood standing there as if he hadn’t died a week earlier. If Pomeroy saw Trentwood, then Mary would know she wasn’t entirely mad, or certainly not delusional. Of course, the danger in ushering Pomeroy inside would be the realization that I am, in fact, losing my wits. Mary bit her lip.

“Why not let the poor man in, make certain you haven’t done harm to yourself?” Trentwood suggested. He had moved to the vanity, taking the seat Mary had not offered to him. He watched her archly, radiating his displeasure with his stiff carriage and the way he picked at the dirt beneath his fingernails.

If I answer him, I acknowledge his existence, and then I’ll know I’m mad. If I don’t answer him, I don’t know either way. Decision made, Mary threw open the door. “Just for a moment, yes, I’d like your company. I find my… thoughts disturb when I’m alone.”

Pomeroy was as tall and lanky as Trentwood, and as old as him, if not older. Mary had no idea, in fact, how old Pomeroy was. She knew only that he had always been her father’s valet, he never had a hair or piece of clothing out of place, and he worried about her as if she were his daughter. And that he was a prize pugilist who was more than happy to teach her a thing or two.

Pomeroy’s hair was completely white and had been so since he turned twenty—something about the shock of losing his sister in a fire. Mary never knew the details and knew better than to ask.

“Thoughts are one’s own enemy at a time like this,” Pomeroy murmured, entering the room.

“Would you care to have a…” Mary’s voice trailed off. Trentwood sat in the only available chair in the room and didn’t look as though he was about to give it up to anyone, especially not his valet. Thankfully, Pomeroy had no plans to sit.

“I’ve only come to say, and do pardon my impudence, that I’m worried about you. We both are, Mrs. Beeton and me. You’ve had a rough year, taking care of your father and your aunt besides.”

Mary nodded once. She crossed her arms over her chest. It rankled, the awkward sounds of kindness about her loss. She hadn’t decided if she was prepared to accept such words yet. Having her dead father in the room didn’t help matters.

Pomeroy continued, stammering a little as Mary stepped away from him. “It was decided I should tell you we will handle the running of the house, to—to ease your burden.”

Trentwood scoffed from his corner. “A lovely sentiment, I’m sure, but what are you to do with yourself if he takes away your one occupation, hmm?”

Mary squared her shoulders. She anticipated Pomeroy to shout, scream, blanch, faint, or all of the above. He did none. He waited for her response, giving no indication that he had heard Trentwood speak, nor revealing any suspicion that anyone but Mary was in the room with him.

This does not bode well for my sanity.

“I must admit the offer is tempting, and so very generous. I am, of course, touched and overwhelmed by your kindness,” Mary whispered, “but I must keep myself busy.”

Pomeroy bowed. “I find it’s best to stay busy, Miss, and be certain to not be alone for too very long.”

Mary risked a sidelong look at Trentwood, who grinned. “Depend upon it; I don’t think I shall be alone often.”

In which Hartwell arrives

Mr. Hartwell was jolted awake, his arms flailing, when the train from London pulled into Swindon. His low-brimmed hat, which he had pulled down to shade his face while he slept, fell to his lap. He heard the snickers of the little boy sitting in the aisle across from him. He knew he should resist the temptation, but he looked at the boy and scowled.

The boy gasped and pointed at Hartwell’s face. “Mama,” he cried, “what’s happened to him?”

The boy’s mother looked at Hartwell, blanched, and slapped her son’s hand. “Don’t point, dearest, it’s rude.” She turned to Hartwell, though he noted she avoided meeting his gaze. “Please forgive him. He’s the most mischievous terror of all my children.”

Hartwell nodded and gathered his things, but not before making a face at the boy for good measure. He couldn’t help it. The boy was a brat, his mother knew it, and Hartwell was in no mood to be someone’s entertainment, child or otherwise. He slapped his hat onto his dark hair, threw his coat over his shoulders, and stomped from the train.

The station was far quieter than the London one he had left that morning. There were still children crying, paperboys shouting, train attendants ushering, and far too many people milling about as if they had no idea where they were going. Well, Hartwell knew where he was going. At least where he needed to get to, and damned if he was about to tarry simply because someone wasn’t sure just which car they wanted to sit in and happened to be making that decision in the middle of his path.

“You there,” Hartwell said to a dirty boy playing by the tracks, “where might I find the manor house at Compton Beauchamp?”

“At Compton Beauchamp, methinks,” was the reply.

Hartwell clamped his jaw. “And where, pray tell, is Compton Beauchamp, exactly?”

“Me Pa can drive you there, if you like,” the boy said, jumping to his feet.

Hartwell stepped back so the upset coal dust didn’t touch his suit. “Take me to your father, and be quick about it. I need to catch the evening train back to London.” He followed the boy, who he discovered was named Peter, to a wagon full of animals. Pigs, of all things, and geese, and sheep. “Oh no.”

Peter bounded to his father’s side and tugged the hem of his frayed jacket. “Gent here’d like a lift to Compton Beauchamp, Pa.”

Hartwell shook his head when Peter’s father squinted at him from beneath his straw hat. “Forgive the intrusion, I thought your son was taking me to the stables.”

“You’ve a pretty way with words, son.” Peter’s father had a voice of gravel. It sounded smooth, yet Hartwell could hear ball bearings tumbling over one another in the undertones. “What are you doing trying to get to Compton Beauchamp?”

“I’ve business with Mrs. Durham,” Hartwell admitted, “and the sooner I get there, the sooner I can return home.”

Peter’s father chuckled and tightened the harness on his farm horse. “I’ll be the only one heading that direction. No one goes to Compton Beauchamp unless they live there.”

Hartwell’s shoulders sank. “Really?” he said, his voice flat.

“Aye, and you’ll be having a trial of getting to Mrs. Durham, what with the goings on at the manor house.”

One of the geese looked at Hartwell and honked loudly at him, finding some offense. Hartwell rubbed his forehead. “What has been going on at the manor house?”

“Well, the young miss lost her father a month ago, and the house is in mourning.”

“Ah, I see.” That certainly posed a problem; they would be in mourning for a year, and Hartwell simply didn’t have that sort of time. He shook his head. “Sorry, I must have misunderstood you. Young miss? Mrs. Durham is forty-five if she’s a day, as I understand it.”

Peter’s father chuckled. “Not her, but her niece by way of her twin, Miss Trentwood. Mrs. Durham’s doing her duty and watching after the girl. Though she’s going through her own mourning.”

“How very noble of her,” Hartwell said through clenched teeth. Well, he had come this far for answers. Certainly he could come and go quickly without disturbing their period of mourning too much. “I should be much obliged then, if I could ride with you to the manor house.”

Peter cheered and scrambled up the large wheel to sit on the wagon’s wooden bench that would seat the three of them.

“I’m Frank Brown,” Peter’s father said, holding his hand out for Hartwell to shake.

Hartwell glanced at the weathered hand, seeing years of dirt encrusted in its folds. He shook Frank Brown’s hand with a tentative smile. “Alexander Hartwell.”

The ride to Compton Beauchamp was, Hartwell found with no little surprise, pleasant. Frank Brown was by no means chatty, but he answered all of Hartwell’s questions amiably enough.

The countryside was the sort of tame green beauty he remembered from his childhood, and Peter, when Hartwell had removed his hat to enjoy the warmth of the sun’s rays on his head, made no mention of his scarred face, which he appreciated.

Even the noisy animals crowded in the back of the wagon seemed to Hartwell a happy respite from the drudgery of London life. It was charming to hear the pigs snort as if scoffing at something the geese said, or the sheep’s low murmuring when the wagon swayed over a bump in the road.

Hartwell marveled at The Great White Horse, an ancient carving in the chalky ground on the hills just outside of Compton Beauchamp. The Browns humored him and drove the wagon up the hill so he could study the horse closely. He shared their packed luncheon of generously cut bread and cured meat while listening to Frank Brown’s folktale that the horse was actually the bones of the horse belonging to none else but William the Conqueror.

In fact, by the time he was dropped off at the pale lane just outside the manor house, Hartwell was so totally enamored with his new friends that he almost forgot why he had come to Compton Beauchamp in the first place. He waved to the Browns as they ambled away, and chuckled at the sight of the pigs, sheep, and geese watching him forlornly from their rocking, wooden cage.

When the wagon was out of eyesight, Hartwell sighed and turned to the high wrought iron gate that provided the only opening to the brick wall surrounding the manor house. The gate was propped open by a sizable rock, so he slipped inside. He squared his shoulders. Better get this over with, Hartwell thought, shrugging to adjust his shoulder cape.

Hartwell walked along the gravel path that was wide enough to usher carriages to the portico that sheltered the front door. The manor house, it seemed, had seen better days.

Far better days, by the looks of it.

The house had a Palladian façade that spoke of modest grandeur. The yellow limestone of the façade was laid in an irregular pattern and was accented by smooth ashlar dressings smartly jointed together. Red brick archways decorated the windows, pulling the eye up to the roof, which sorely needed repairing.

Hartwell tugged the embroidered bell pull hanging just right of the door and waited. And continued to wait, hearing neither a bell, nor anyone coming to open the door.

He yanked the bell pull again. This time it snapped in pieces into his hand.

His mouth dropped open. Frowning at the portico and seeing finger-sized cracks in the plaster, Hartwell lost confidence, what with the remnants of the bell pull dangling from his fingers. He rapped his knuckles against the front door and jumped away just in case the portico decided to fall on his head.

Finally, Hartwell thought he heard someone approach the door. He heard concerned mumblings. Whoever was behind the door continued to mumble for a full five minutes. He tapped his leg with the bell pull impatiently. “Oh, for heaven’s sake, will you open this door?”

The voices fell silent.

He hadn’t expected them to hear him.

The door creaked open to reveal a tall, lanky man with a shock of white hair and a woman with a cap of white lace atop her graying hair. They both wore black, reminding Hartwell that the house was in mourning. Their solemnity seemed out of place with the fine weather tickling the hairs on the back of his head. I ought to have sent a letter ahead.

The two persons stared at him, and Hartwell realized they wanted him to explain himself. He reddened. “I’m Alexander Hartwell, and—.”

The woman lost all color and slammed the door in his face. She, he assumed, was Mrs. Durham.

He knocked on the door again, relieved this time when the man opened the door, the woman was nowhere in sight.

“Do come in, sir,” the man said. “I believe Mrs. Durham has fled to her room. If you would wait in the library, I will send for my mistress.”

“Then Mrs. Durham is not the lady of the house?” Hartwell asked as he entered with a small frown.

“No indeed.”

“Excellent.”

“Yes indeed.” The man smiled at Hartwell’s apparent surprise. “I’m Pomeroy, the butler and valet to Mr. Trentwood that was. If you’d be so kind as to wait in the library, I shall send for Miss Trentwood and have a pot of tea sent to you.”

Hartwell allowed Pomeroy to take his hat, coat, and satchel, relieved to be rid of the carried weight. He ignored the way Pomeroy started at the sight of his face, already building up his tolerances as he followed Pomeroy to the little library just off the main hall. I’ve been so used to being with people who are used to me, he thought with a disgruntled sigh.

“Miss Trentwood will be in shortly,” Pomeroy said.

Hartwell nodded, and handed Pomeroy the bell pull. “Er… do apologize in advance to Miss Trentwood for me?”

Pomeroy stared at the bell pull in his hand, and his face tightened as if he was trying not to laugh. He cleared his throat. “We haven’t had visitors in quite some time, sir.”

“I never would have guessed,” Hartwell replied.

In which Pomeroy deflects

When a girl loses her father, no matter her age, whether in the school house, married, or a spinster like Mary, she wants to mourn. She wants to take time to remember the most influential man in her life, if she has been blessed enough to have the influence of her father, if she has been blessed enough to have a father who cares enough to have an influence on her.

She wants to look back on times of laughter with fondness, and times of punishment with sheepishness. She wants to give credit where it is due, and take the time to put his dearest possessions away for moments of tearful reminiscence.

Admittedly, Mary had not been looking forward to life after her father—especially when faced with the unfortunate truth that she would have to face it with her aunt, of all people. For all her disappointment regarding Steele, Mary had been glad to read to Trentwood every night and guarantee that he had eaten enough during their meals.

Despite his sometime pigheadedness, Trentwood had been a generous and encouraging father.

He hadn’t liked to read, but he had indulged Mary’s obsession with books precisely because her mother had done the same. He had preferred to ride rather than walk, and Mary the reverse, so, rather than shuffle the duty to Pomeroy or a footman, Trentwood had joined Mary on her walks to Wayland’s Smithy, the collection of sarsen stones at the edge of Compton Beauchamp.

Life with her aunt would not be so easy.

The sound of slamming doors roused Mary. She had been staring through her bedroom window in the direction of the family plot where her father, supposedly, had been laid to rest.

She shifted her focus to her reflection, not liking the sight of her bloodshot eyes and the bags beneath them, or the hollows in her cheeks. She tucked a stray strand of hair behind her ear and sighed. “What would Steele think of me now?”

“You’re still on about that chap?” Trentwood said.

She jumped from the window because she couldn’t see Trentwood well enough. She had yet to respond to him, though he had haunted her a month. She had hoped, futilely, that he would leave her alone if she ignored him long enough.

“You aren’t mourning me at all, are you? You’re mourning that fop, aren’t you?”

I can’t take this for much longer, Mary thought, clenching her hands into fists at her side.

“I trust someday you’ll see the sense in what I did.”

Mary glared at Trentwood, or his ghost, rather, and strode to her bedroom door. Better to investigate the mysterious slamming doors than answer him and confirm her fears of insanity.

Mary threw the door open and yelped. Pomeroy stood there, silent as ever, his hand raised to knock.

“Sorry to disturb, Miss, but—”

“What is that?” Mary said, pointing at Pomeroy’s hand.

“The bell pull, miss.”

Mary swallowed. Her mother had embroidered that bell pull; it was the last thing she had completed before her death. “I see that, I was wondering what it was doing in your hand.”

“It seems to have fallen apart, miss.” Mary could feel her face fall, and so wasn’t surprised when Pomeroy continued in a conciliatory tone, “It is rather old, miss. Almost twelve years.”

Mary nodded, taking it from him. “Very well. I’ll begin work on a new one immediately.” She glanced down the hall. “Was that Mrs. Durham’s door I heard slam? Don’t tell me she didn’t get her tea on time this morning.”

“Mrs. Durham, it seems, is hiding from the person who ruined the bell pull.”

Mary shook her head. “You aren’t making sense.”

“I don’t know much more, Miss, I’ve asked the gentleman to wait in the library.”

Mary stopped mid-nod. She looked at the decimated bell pull in her hand. “You mean someone destroyed the bell pull, and you sent him to the library? My library? And that my aunt is hiding from said person?” She lifted her black skirts and rushed down the hallway. “Pomeroy! What if he does something to my books?”

“I don’t think that’s Mr. Hartwell’s intention,” Pomeroy said, his voice suspiciously even-toned as he followed her.

Mary stopped halfway down the staircase. “Hartwell?”

“I took the liberty of looking through the late master’s correspondence book,” he said, slowly, “and found no mention of him. Whoever Mr. Hartwell is, he’s known to Mrs. Durham alone.”

Frowning, Mary tapped her lower lip and pondered a moment. “And he asked for me?”

“No, Miss, he asked if Mrs. Durham was mistress. When informed otherwise, he seemed most pleased.”

Mary groaned softly. “It must be a representative of father’s solicitor. I was written he would arrive soon.”

She peered around the stair banister at the library door at the end of the first floor. They had kept their voices low, so the mysterious Mr. Hartwell probably hadn’t heard them. She wrinkled her nose. Mary didn’t like to think of herself as cowardly, but she just couldn’t stand the idea of speaking with her father’s solicitor, not knowing if or when Trentwood’s ghost might appear.

She nodded, her mind made up. “Make my apologies. Give him a scone or something.” Mary ran up the stairs she had recently scurried down.

“And what should I tell him?” Pomeroy said, trailing her, irritation deepening his voice.

“That I’ve a headache. It always worked for mother.” Mary darted into her bedroom, threw her dolman around her shoulders, snatched her hat and some hat pins, and smiled an apology at Pomeroy. He watched her with a frown.

“I suppose my telling you that your father would disapprove will do nothing,” Pomeroy grumbled.

Mary kissed his cheek. “Not a thing.”

“Or we haven’t the resources to send a footman with you?”

“I’m twenty-seven, Pomeroy, I don’t need a chaperone.”

“A chaperone, no. Protection, yes.” Pomeroy flushed and ducked his head. He knew better than to argue with Mary when she was in this mood. “Be careful out there; Mrs. Beeton says a storm is coming.”

Mary pinned her hat to her head and pulled the veil made of black netting down past her chin. “I’ll just have to get to Wayland’s Smithy before the clouds open then, won’t I?”

With that, Mary slipped out the back staircase, startling Mrs. Beeton and her dilapidated kitchen in her escape.

Clouds, dark and thick, descended over Mary as she crept along the manor house wall beneath the library window, hoping she did so unseen. She waited until she was out of earshot before dashing down the gravel drive to the high wrought iron gate. Her black skirts swirled around her ankles. She slipped through the gate, looked back at the manor house, and sighed.

“Not really what it used to be, eh?”

Mary yelped for the second time that day and jumped away from the voice. She grimaced, having scraped her back against the brick wall enclosing the Trentwood property. Hand at her bosom, she snapped, “Will you stop doing that?”

Trentwood stepped through the wall and gave her a half-hearted shrug. “So now you’ve decided I’m real?”

“I’ve decided no such thing, I’m simply tired of being caught unawares,” Mary retorted.

Trentwood grunted. Whether real or not, his mimicry of the man was uncanny. “Where are you off to?”

Mary spun on her heel, turning her back to Trentwood as she walked down the pale English lane, where the very last remnants of autumn’s leaves spun and danced with an eddy. Unable to hear footsteps, Mary glanced behind to be certain Trentwood was (or was not) following her.

He was. Mary stumbled through the hedgerow, heading southeast of Compton Beauchamp proper. Brambles clung to her skirt and she yanked it free.

Mary’s breathing became labored—she had halted her walks during Trentwood’s illness and so was a year out of shape. It was a cold day for March, and her breath left little white cloud bursts in the air. She glanced behind her. Trentwood persisted.

“At least he’s being visible about it,” Mary muttered. She stomped across the farmer’s field to the copse of trees shading the sarsen stones—much like Stonehenge—stacked together to make the ancient tomb known as Wayland’s Smithy.

She stumbled to the front step of the yawning opening in the ground. She sat though the step was covered with lichen and moss. Mary had been coming here for years, but she had never once worked up enough courage to venture inside the tomb. It was something Trentwood never failed to—.

“Still don’t have the courage to step inside, eh?”

“If you aren’t my father, you are eerily similar.”

Trentwood chuckled and sat beside her. He never made a noise when he moved. That was the worst of this whole business, Mary decided. She could handle the smell and liked that it alerted her to his presence. His low, serious voice, something else Mary had inherited from him, had remained as she had remembered it. And he looked as he had at his peak, which brought a certain sort of comfort… once she had gotten past the idea that he was supposed to be dead.

“Do you think you could… erm, wear a bell?” Mary said, kicking her legs out before her and smoothing her skirts. She avoided looking at Trentwood.

His eyes—she couldn’t abide his eyes.

“You would have me wear a bell, like a dog?”

Mary scowled at his indignant tone. She should have known better. He was supposed to be her father, after all. “Of course not, you’re right, how silly of me.”

They sat together in an awkward silence, the wind blowing Mary’s veil across her face. The wind did not affect Trentwood in the slightest.

“So you aren’t going to ask why I’m here?” Trentwood said, breaking the silence after ten minutes or so.

Mary lifted her veil with great reluctance to meet him, eye-to-clouded-eye. “No.”

“You aren’t the least bit curious?” Trentwood prodded.

“Oh, I am,” Mary admitted ruefully, “just not enough to ask about it.”

A branch snapped, making Mary jump.

“Who are you talking to?”

In which Hartwell pursues

Hartwell paced the library for half an hour while waiting for Mary. He kept his hands clasped in a tight fist behind his back. He frowned not because he had been kept waiting, but because he had no idea what he was going to say once Mary entered. Everything had seemed quite simple when he had left London that morning.

He had assured his sister he would return for dinner. That was before he had realized Compton Beauchamp was in the back of beyond, and his quarry was a rude little middle-aged woman.

Well, to be fair, Hartwell had expected the latter. He couldn’t think of anything kind to say about Mrs. Durham, though his sister proclaimed fond memories of their school days together.

Never mind all that, back to the task at hand: how was he to explain his presence?

When the library door opened, Hartwell turned in nervous anticipation. He didn’t think Mary would look favorably on the fact that he had scared her aunt to some undisclosed location in the manor house. Luckily, it was not Mary but Pomeroy with the tea who entered.

Hartwell’s frown deepened, this time with genuine displeasure.

“Miss Trentwood begs your pardon, sir,” Pomeroy said as he settled the tray on a side table. “She’s been suffering a terrible ache and cannot meet you today.”

Hartwell opened his mouth, ready to say a thing or two to Pomeroy about his Miss Trentwood, when a distinctly female-shaped form clad in all black scampered into the periphery of his vision. Brows raised, Hartwell faced the window just in time to watch Mary slip through the front gate, having practically sprinted from the manor house.

Well, then. Hartwell grinned at Pomeroy, who was preparing the tea far too studiously.

“I take it that was Miss Trentwood?” Hartwell bit out.

“Yes, sir.”

“And she has a terrible ache, is it?”

“Yes, sir, of the leg.”

“An ache of the leg.”

“Yes, sir. She ached for a walk.”

Hartwell rubbed his forehead. “Oh, for the love of—do you know where she’s heading?”

“I couldn’t say, sir.”

Hartwell waited until Pomeroy met his cold expression. “Hazard a guess.” He watched Pomeroy look him over, trying to size up his pugilistic abilities. Doing as any other man had done since his accident, Pomeroy stopped at the sight of the scar on Hartwell’s face. Beyond that, Pomeroy looked directly into Hartwell’s eyes, long enough for Hartwell to shift his weight in unconscious discomfort.

Whatever Pomeroy saw in Hartwell’s face, he must have approved. “If I had to hazard a guess, I would say she’s taken a right down the lane, cut across the field, through the hedgerow, toward the gathering of trees southeast of here. If I had to hazard a guess, sir.”

Hartwell blinked at Pomeroy, who did the same in return. “Oh. Well. Thank you.” He grabbed his hat and coat from the chair where Pomeroy had settled them earlier. A funny expression on his face, Hartwell strode from the library in pursuit of Mary.

“I trust you will ensure her safety given that you have business with her, Mr. Hartwell?” Pomeroy said, following him to the front door. His tone made no mistake about his meaning.

Hartwell bristled. “Yes, of course.”

“Very good. I’d hate to have to kill you.”

Again, Hartwell blinked at Pomeroy, who again did the same in return. Hartwell swallowed when Pomeroy maintained a steady gaze, while his faltered. “Right,” he muttered, slapping his hat to his head.

“Take this,” Pomeroy said, handing Hartwell a woolen blanket from behind a hidden door in the hallway, “in case she refuses to return before the storm hits.”

Mouth agape, Hartwell accepted the blanket, too surprised to refuse it. “Just how often does she do this?”

Pomeroy opened the door. “Best be going, sir, or you’ll not beat the storm.”

“You’re really sending me out there after your mistress? A complete stranger. With a blanket, of all things?”

Pomeroy’s smile chilled Hartwell almost as much as his reply. “No need to worry about her. She’s haunted. And her father’s more protective than I am.”

Mind racing, Hartwell wet his lips with a drying tongue. What was it Frank Brown had said about visiting the manor house? That he would have a trial of it? That the master had recently deceased? “I was brought here by a Frank Brown. He told me Mr. Trentwood had died, of late.”

“Frank Brown is correct.”

Hartwell narrowed his eyes.

“I suppose one has to be dead, sir, to haunt one’s daughter.”

Hartwell exhaled. “Do you treat all your guests like this?”

Again, Pomeroy smiled. “You’re the first guest we’ve had in quite some time, sir, excusing the funeral, of course.”

Flabbergasted, Hartwell let Pomeroy usher him from the manor house. After the door shut in his face, blanket in hand, he debated chancing a walk back to Swindon, damn the consequences.

Except that wily butler still had his satchel, with all his money and papers.

“Holy hell, Frank Brown was right about this not being easy!”

A timid raindrop splashed on Hartwell’s hat brim. He scowled at the gathering clouds. It was most definitely going to rain, and he was most definitely going to be caught in it. Did that butler give him an umbrella? Oh no, that would have been far too sensible, and what did sensible thinking have to do with a house governed by a haunted lady?

Nothing, that’s what. Absolutely nothing.

Hartwell felt so exasperated he could have stomped his way down the gravel drive, through the wrought iron gate, and down the English lane to find Mary. But Hartwell was sensible and knew that stomping that distance would exhaust him, let alone take far too long. Hartwell threw the blanket over his shoulder, shaking his head. He knew what he was in Compton Beauchamp for, he just wasn’t sure it was worth all this nonsense.

Hartwell had little difficulty following Mary’s hasty retreat to the lonely gathering of trees in the middle of an empty pasture. He slowed his pace at the end of the clearing in the middle of the trees, hearing voices.

Rather, not voices, but one low voice, carrying a stilted, one-sided conversation.

Hartwell ducked behind one of the larger beech trees and shivered in the cold. On the front step before an opening that seemed to lead underground sat a woman in all black. She was looking to her left as though listening for something.

To something.

To someone?

She lifted her veil with trembling fingers. Hartwell was too far away to see her face clearly. This was definitely Mary Trentwood, however. He couldn’t think why that rascal Pomeroy would lead him elsewhere.

The wind blew, racketing a shudder through Hartwell, who hadn’t dressed for chill weather. Had he not been so cold, he might have held onto his exasperation. There was something frightening about the way Mary spoke to herself. It was almost as though she believed she was haunted.

“Oh, I am,” she said to nothing and no one. “Just not enough to ask about it.”

Hartwell stepped closer to get a better look. He winced when a branch snapped beneath his foot. He swallowed when she swiveled to fix her serious, alarmed, hazel gaze at him. Oh well. Best to satisfy his curiosity and hope the answer would alleviate the queasiness in his stomach.

“Who are you talking to?” he asked, stepping into the clearing.

Mary jumped to her feet. She readjusted her veil so it guarded her face. “Who are you? Are you following me?”

The panic in her voice reminded Hartwell that if she was haunted, then the last thing he wanted to do was raise the ire of her ghostly father. He shook his head. What am I thinking? There are no such things as ghosts. I’m tired, that’s all.

“My name is Alexander Hartwell. I watched from the library window as you escaped the manor house.” He held up the blanket. “Your butler sent me with the message that a storm is coming.”

He wasn’t sure, what with the veil masking her expression, but Hartwell thought Mary might have allowed a wry smile before a blush crept over her cheeks.

“Well,” Mary said, “if Pomeroy sent you, then I suppose I’ll have to speak to you, shan’t I?” She didn’t wait for his response before reclaiming her spot on the stone. She brushed her skirts briskly, arranging them until she was satisfied, and looked at Hartwell expectantly.

Hartwell stepped closer, incredulous. “You want to talk here?”

“What’s wrong with here?” Mary looked around the clearing, though what she saw in it, Hartwell had no idea. “It’s quiet here.”

Hartwell frowned at the sarsen stones, the way they were stacked like a deck of cards to make a shelter, of sorts, but with a flat top. “It looks like a tomb.”

Mary shrugged and flicked a speck of dust from her skirt. “I think it is.”

“It is what?”

“A tomb.”

“And you see no problems with holding a conversation here?”

“Not at all, it’s very quiet here, we won’t be interrupted.”

“That’s because it’s a tomb,” Hartwell exploded. He was going to continue, but the tree boughs swayed overhead. Not a good sign. True to his suspicion, the rain began to pour onto his hat and shoulders. He grunted.

Mary stood, brushing off her backside, and turned to stare at the tomb’s opening. If anyone was buried there, they would be nothing but bones. But still she hesitated. The woman had obviously lost her mind, Hartwell figured, or was somehow still in shock over her father’s death. Indeed, the latter explained the ghost farce quite nicely.

In any case, Hartwell, having had the misfortune of having to stand through too many rain showers, saw no reason to stand through this one. He threw the woolen blanket over his head and shoulders before dashing to Mary’s side. He grabbed her by the arm and dragged her inside the doorway of the tomb.

“For someone who seems quite averse to the idea of tombs, you’re rather ready to jump into one,” Mary said. She pulled away from Hartwell to crouch as close to the doorway as possible.

There was hardly room for standing in the little cave-like structure, and it smelled of mildew. Better that than decomposing bodies, Hartwell thought darkly. He stooped, his shoulders scraping the top sarsen stone. He shuddered to know what his coat would look like after this unforeseen romp.

There was a bed of rotting leaves beneath their feet, adding to the sickly sweet smells assaulting Hartwell. A gust of wind threw a sheet of rain into the tomb, and Hartwell backed away from the opening. Mary, however, remained where she stood.

Hartwell clamped his jaw. “Would you rather stand in the rain and catch your death of cold than stand beside me?”

Mary gave him a steely glare. “I will die eventually, Mr. Hartwell, but it won’t be from catching cold, not if I can help it.”

Hartwell resisted the urge to scratch his head, puzzled as to why he felt he had royally put his foot far into his mouth. Maybe it was the way Mary’s shoulders were hunched. Or the way she was inching as close to the door as possible, and therefore as far away from him as she could get without venturing into the rain. Or maybe it was the way she had said, “Not if I can help it.”

He still couldn’t see her face very well, what with the veil firmly in place. But then, he didn’t need to see her face to talk to her.

“Miss Trentwood, I feel we’ve started on the wrong foot.”

“To say the least,” she replied.

She had no reason to be so terse with him, she could have no idea why he was in town. As he mulled over her reactions, he realized he was still holding the blanket over his head.

Mary looked very little standing there, rocking back and forth ever so slightly, shivering as she hugged herself. It must be her mourning weeds that made her so small—she looked nearly his height, and he was tall by anyone’s measure. Ashamed by his callous behavior, Hartwell stepped close enough to wrap the blanket around Mary’s shoulders gingerly. She stiffened, but when he stepped away, she relaxed. Marginally.

“Well, we won’t be going anywhere anytime soon,” Mary said. “Why don’t we share the blanket and you can tell me why you destroyed my mother’s bell pull, frightened my aunt so that she locked herself in her bedroom, and dragged me into this tomb.”

Mary looked at him then, her hazel eyes transfixing him. “Whatever it is, it must be very important.”

Hartwell coughed. In all his thirty-five years, he had never been as uncomfortable as this moment. He couldn’t tell her the real reason. For all he knew, she was part of the plot.

No, he wouldn’t tell her the truth, but some approximation of it. Something close enough to the truth that he could remember the details, as he had always been, and probably would continue to be, an awful liar.

“My sister was schoolmates with your aunt, Mrs. Durham,” he began.

“What?”

Hartwell repeated himself, unsure why Mary frowned so.

“Then you’re not my father’s solicitor? Or related to him in any way?” Mary asked, her voice flat.

Hartwell’s responding frown wavered, then exploded into an understanding smile that threatened to become a laugh. Hartwell liked to think her voice was flat with embarrassment and a sort of sheepish dismay.

“You thought I was a solicitor?” At Mary’s nod he did laugh, a little. “No wonder you ran away.”

“I didn’t run away, I went for a walk.”

“A walk to a tomb.”

“It’s my favorite spot. No one bothers me here, usually.”

Hartwell didn’t mistake her meaning. “I’ve come, Miss Trentwood, at the behest of my sister. She heard of your sorrows, from your aunt, I assume.”

Mary stood very still, her neck craned to see him. It was obvious she hadn’t noticed his scar yet. She still considered him an annoyance rather than someone to be feared. He had every intention to use this to his advantage, and made sure to stay shadowed as long as possible.

Mary shifted, pulling the blanket closer around her shoulders. “And what does your sister intend for you to do, Mr. Hartwell?”

“My sister has asked me to help in any way I can, being such friends with your aunt. Perhaps,” he said, hesitating slightly, “when the real solicitor’s representative arrives I can be of service?”

“So you are familiar with solicitors, then?”

“Oh yes, my father was one.”

“That only makes you familiar with the person. What does that mean in terms of a solicitor’s business? I thank you, but no.”

Hartwell inhaled, not expecting such a blast of sharp logic thrown at him. He fought the urge to study her expressions and guess her responses before she had the chance to make them. She was the trial, he realized, that Frank Brown had warned him about. Not the death in the family, not the unwillingness of Mrs. Durham, but Mary Trentwood.

She had a logic that rivaled many of his schoolmates. That rare sort of common sense that cut to the point and left casualties in its wake.

“I am often in the company of solicitors, Miss Trentwood,” he began.

“Do you often require their services?”

“Yes,” Hartwell snapped, “I do. I’m a barrister, Miss Trentwood. It is my profession to require the services of solicitors.”

Mary was quiet far too long for Hartwell’s liking. She seemed to be looking behind him, listening intently to something he couldn’t discern. Her expression seemed to go slack for a moment, and then tightened as though she had just heard most unpleasant news. When she spoke, finally, Hartwell jumped, bashing his head into the stone ceiling.

“Well,” Mary said, pausing for him to shake away the stars from his eyes. “First, you better sit down in case you’ve hurt yourself.” She scooted to the side ruefully, giving him room to plop beside her.

Hartwell hesitated. She had given him space to sit to her right, which would have put his scar in view. For whatever reason, he wanted to postpone the unveiling; he was, he found with great amusement, enjoying her odd manner of speaking. He didn’t want to discourage this frank dialogue by startling her. He sidled to her left and waited for her to shift positions to afford him a space to sit. She did so with her brow wrinkled in confusion.

“Second,” she continued, the way a prodded child might, “you might as well stay for dinner, since you’ve come all this way.”

Still rubbing his head, Hartwell said, “Thank you. What’s the third item?” It sounded as if Mary wasn’t quite finished.

“Third, I don’t believe your story about your sister, and I don’t like you, but we’ll have to see what my aunt says, given her supposed history with your family.” She glanced at him with a very slight curl in her lip. If Hartwell hadn’t been looking, he might have missed it altogether. “Pomeroy saw something in you, though I’m not sure what, so I’ll have to give you a chance, I suppose.”

Hartwell’s mouth dropped open. What a pert mouth on this one! Had it been anyone else, he might have given them the benefit of the doubt and excuse her manners for grief or shock. But the words and tone came too easily—this was how she was, he suspected dourly.

“Technically,” he said, keeping his tone light, “wouldn’t those be items three, four, and five? You had conjunctions in there.”

Mary narrowed her eyes at him.

“Oh look,” she said, “the rain is letting up. Do let us return and show Pomeroy he doesn’t get to hurt you.”

“Oh yes, let’s,” Hartwell said sarcastically.